Westbrook: A NBA Career Retrospective

You want success as a running back on the gridiron?

You need vision.

Not eyes. Instinct.

See the crease before it exists.

You need burst.

Opportunities don’t wait.

Hit the window before it shuts.

You need to weaponize contact.

Invite the collision.

Leave with more than you brought.

You need to carry it.

Not the ball—

the moment.

You need awareness.

Know when they're your yards—

And when to pitch it.

You need heart.

A refusal to go backward.

Every fall is forward progress.

Now swap turf for hardwood. Uprights for a rim.

That’s Westbrook.

A crease-hunting downhill decision

who’d rather be wrong at full speed

than safe at half.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

On Wednesday, January 21, 2026, the Kings held a special ceremony to recognize that Russell Westbrook became the all-time scoring leader among point guards, surpassing Oscar Robertson’s 26,710. He remains about 600 points ahead of Steph Curry. Russell Westbrook may or may not be retiring. Depending on who you believe, it’s next summer. Or the one after that.

Either way, the hour is late. The question has shifted.

He’s one of the most divisive players of his era — and also a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Since leaving Oklahoma City, he's been passed around like a closing time bar tab nobody wants to pay -- six teams in seven seasons -- despite being the all time leader in triple doubles.

He’s been ridiculed by columnists, heckled relentlessly by fans, and yet he’s also lifted an MVP trophy and dragged entire franchises somewhere they had no business going.

Those things coexist. Uncomfortably. Honestly.

So, while we can still watch him operate in nonstop, chaotic motion — while the motor is still humming and the collisions are still coming — we felt it was time to ask the real question.

What mark will Russell Westbrook leave? What is his legacy?

To answer that, we should kick things off at the beginning.

FIRST DOWN

The Statement

“I grew up wanting to play football.

I played running back and linebacker.

I liked linebacker better. I liked to hit people.”

Russell Westbrook didn’t grow up imagining MVP speeches. He grew up taking buses across Los Angeles, hopping off near parks, and playing whatever game was being run that day. Sometimes it was organized. Most of the time it wasn’t. Concrete courts. Bent rims. No refs. No whistles. You stayed upright or you went home.

When he talks about football, it’s not nostalgia. It’s memory. The hitting. The collisions. The pace. The idea that effort was never optional. He never made it farther than Pop Warner league, because a growth spurt affected his coordination at a time that cost him momentum into football, he'd later say. Fortunately, Russ had been cultivating more than one athletic skillset, under the guidance of his father.

Russell Westbrook Sr. was his first coach in every way that mattered. He taught his boy the one skill that had never let him down: work ethic. Structure. Repetition. Sweat. They didn’t “work out.” They trained; pushing limits to add muscle and stamina.

They didn’t “shoot around.” Russ would practice shots from the same spots like a piano prodigy practices scales. Hundreds of shots. Until the mechanics were automatic.

At the same time, his parents were doing something else just as deliberately: keeping their sons safe. Because downtown Los Angeles was far from the glamour of the Hollywood Hills. Structure and drive were a bulwark against idle hands and the wrong crowd.

Family was the center of everything. Still is. Westbrook calls his parents every day. Before games. After games. On the road. At home. That’s not branding; it's Russ.

He watched their marriage. He’s spoken about the stability of it. The absence of chaos. The way conflicts didn’t become performances. It shaped how he talks about his own family now. What he protects. What he doesn’t entertain.

While his father provided his first set of tools, and his mother made sure he stayed well-rounded. She was the academic enforcer making sure the brothers remained honor students even once they got to university. And when Russell would become discouraged about his prospects of making the college team, or the NBA draft, she would challenge him: “Why not you?”

Russell Westbrook wasn’t a blue-chip Division I recruit. Not even close.

He was ranked 151st in the class of 2006 — a fringe national prospect. Plenty of evaluators thought he was a better fit for the WCC than the Pac-10. Some openly questioned whether UCLA was out of his depth.

He had options. Stanford offered a safer path. Cleaner projection.

He'd decided on UCLA long before he had the résumé to justify it. It was down the road. A tangible path out of the inner city. Close enough for his family to make every game.

And the doubters who said he couldn't cut it there? He loved proving them wrong.

UCLA's men's basketball coach, Ben Howland, didn’t recruit him because he was polished, or a sure thing. He saw leadership, passion for the game. And in his non-stop energy, he saw the potential for a great defender.

When Russ arrived on campus, he wasn’t a star. He could barely crack the rotation, stuck behind Darren Collison. He quickly figured out that his scoring wouldn't get him a bigger role — but hustle did.

So he became the gap-filler for the Bruins. The one who picked people up full court, dove to the floor for loose balls, boxed out bigger men for rebounds. A chaos agent who blew up actions before they developed.

By year two? Starter. Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year. And now the NBA was calling.

When Russell Westbrook entered the 2008 draft process, nobody agreed on what he was. He was labeled a combo guard, which is usually draft-speak for “role unclear.” Scouts liked the athleticism. Loved the motor. Trusted the defense. But they didn’t trust the rest. The concerns were familiar even then: Too reckless with the ball. Too reliant on speed. Jumper was inconsistent. Needed to “learn how to run a team.”

He had started only one season at UCLA. He averaged 12.7 points. What he was — and what every scouting report agreed on — was relentless. Gym rat. Coachable. Obsessive worker. Uncomfortable to play against.

Sam Presti, then the young general manager of the Seattle SuperSonics, saw something in that. Held private workouts. Asked other prospects who the toughest cover was.

Mock drafts had Russ going late lottery. Picks ten through fourteen. Safe range. Sensible range. Developmental range.

June 26, 2008. NBA Draft, Madison Square Garden

David Stern returns to the podium with the next envelope. “With the fourth pick in the 2008 NBA Draft… the Seattle SuperSonics select… Russell Westbrook from UCLA!”

The room reacts like it got told it's free pizza day, and the pizza is anchovy. Loud, but more than a little alarmed.

Russ stands up and hugs his people. Mom. Dad. Tight, quick. No performance.

Across the way, Seattle's Rookie of the Year Kevin Durant is smiling and clapping.

While Westbrook poses for pictures with the commissioner, the broadcast team is already damning him with faint praise: “12 points, four assists… This guy was a late bloomer. He did not start on his high school team until his junior season. Now he’s the fourth overall pick in the NBA draft.”

After the break, Stephen A. Smith catches him live and tosses him the first label of his career. "Jeff Van Gundy says you’re not a traditional point guard. What are you?"

Russ doesn’t flinch. “I’m a point guard.”

Westbrook? He's already Westbrook, thanks for asking.

Seattle's identity is less clear. They would use the 24th pick to grab Serge Ibaka, and then promptly began packing to relocate the team to Oklahoma City as the Thunder.

One blank slate, two young stars, the future wide open.

SECOND DOWN

Still Early

Russell Westbrook arrived in Oklahoma City the way he arrived everywhere else: loud, fast, unfinished.

The Thunder were brand new. Not metaphorically new. Literally new. A franchise ripped out of Seattle and dropped into a city that had never had a team of its own — although it did host the Hornets for two seasons after Hurricane Katrina. There was no culture to inherit. No tradition to lean on. No expectations beyond “try not to be terrible.”

They were terrible anyway. Twenty-three wins. A roster built out of teenagers and maybes. Westbrook started from day one and immediately looked like someone trying to play the game at a speed his own body hadn’t agreed to yet. He charged into defenders. He jumped before he knew who he was passing to. He turned the ball over constantly. The mistakes were frequent and obvious.

So was the pressure.

Even then, you could feel it. Guards didn’t like bringing the ball up against him. Veterans didn’t like getting picked up full court by a rookie who played every possession like it owed him money. Coaches didn’t love the chaos. Teammates didn’t always love the chaos either. But nobody missed the effort.

And then the team started getting better.

Kevin Durant became his true form: a seven foot offensive weapon with guard gravity and an impossible release point. James Harden arrived, himself a stat-stuffing category killer at shooting guard. Serge Ibaka developed into a Swiss Army big. Wins were stacked. The league slowly noticed that the Thunder weren’t a cute story anymore; they were a problem that had been constructed on purpose.

By 2012, the team didn't feel young and inexperienced — they were explosively anthletic and ahead of schedule. The eye test said they were dangerous.m; nobody saw them as an easy out. A 47-19 record in the lockout-shortened season put them in the playoffs as the two seed.

They swept the defending champion Mavericks in the first round. Dallas couldn’t handle the pace. Jason Kidd and Jason Terry couldn’t handle Westbrook’s pressure. In Game 2 Westbrook put 29 points on them, including a clutch three pointer and free throws to close out the 102-99 win.

The Lakers were next. The remnants of a dynasty, still enormous, still dangerous, still armed with Kobe, who had won back to back titles just two seasons prior. Westbrook didn’t treat them with reverence. He led all scorers in Game 1 with 27 points on route to a 29-point blowout win. He blew by Kobe Bryant and Ramon Sessions so often that the Lakers were workshopping new defensive sets in the playoffs, in hopes of containing the damage. In Game 4 with the Thunder trailing in the fourth, Russ exploded to secure the win, finishing with 37. Thunder in five.

San Antonio waited in the Conference Finals, riding a 20-game winning streak and looking every bit the part of a serious one-seed problem. The Thunder lost the first two games. Then something flipped. The series shifted into Westbrook’s rhythm. He controlled tempo. He controlled pressure. He controlled moments. In Game 4, with the season on the line, he detonated the arena with a coast-to-coast and-one dunk that put the exclamation mark on a 15-point comeback. Oklahoma City in six.

Headed to The Finals, Russ now had a new title: Western Conference Champion. He was 23 years old.

In the Finals against Miami, the Heat were under existential pressure. LeBron, Wade, Bosh. Title or embarrassment. Dynasty or disappointment. The Thunder were supposed to be early — too young; a year away.

Game 4 is where the truth of Russell Westbrook lives forever. Kevin Durant got into foul trouble. The offense collapsed. Westbrook responded by becoming a force of nature. He scored 43 points. He hit impossible shots. He took over entire stretches of the game. The Finals had become a one-man performance with twelve million witnesses.

And then, with 13.8 seconds left in a one-possession game, he committed the foul. A mental lapse. A rule mistake. An unnecessary intentional foul that allowed Miami to ice the game at the line. The Thunder lost. The series slipped away.

It is the cleanest possible encapsulation of Westbrook you will ever find: overwhelming force and costly error living inside the same night, the same quarter, the same possessions. Brilliance without reservation. Consequence without negotiation.

That summer, the core changed. A dispute over pay saw James Harden traded to Houston for futures.

The next two seasons would see Russ miss 50 games to injury. This broke a streak of durability: Russell had not missed a single game in High School, not one at UCLA, and had played 439 games straight in the NBA. His streak had been the longest-running in the league. In 2015, Durant also missed significant time, and the team missed the playoffs.

Fair or not, Scott Brooks was replaced as head coach by Billy Donovan. Russell had developed a tight "Ride or die" bond with Brooks, and Brooks consistently defended him to the media, showing unwavering trust in Westbrook. Donovan was less a players' coach and more a tactician. He and Russ would have some growing pains adjusting to one another.

THIRD DOWN

Execution

The 2015-2016 season not only saw a new coach at the helm but it saw Durant and Westbrook in a return to form after battling injuries. It clicked. 55-27 in the regular season, they entered a playoff gauntlet that felt like a Greatest Hits mixtape of their 2012 run.

Their first round opponent? The Dallas Mavericks again. They went down in five.

In the Semi's, once again Tim Duncan's Spurs would present a problem. The 67-win veteran team would deliver a Game 1 blowout; Thunder would lose by 32. Defensive adjustments by Donovan shifted the tone, and Oklahoma City fought back into the series. Again Russ would put his stamp on the series with a massive and-one dunk late in the fourth quarter of Game 5. Game 6 saw the Thunder advance 4-2, and also saw Tim Duncan play his last game — he retired that summer.

Oklahoma City entered the Western Conference Finals as underdogs against a 73-win Golden State team that felt less like a champion and more like an inevitability. The Warriors were supposed to be untouchable. The Thunder didn’t play them that way. They played them like prey.

Game 1 in Oakland set the tone. Westbrook’s shot wasn’t falling — 5 for 21 — and yet he still took over the game. Twenty-seven points. Twelve assists. Seven steals. Steph Curry spent most of the night trying to get free from a defender who refused to let him breathe. Oklahoma City stole home court not with finesse, but with suffocation.

When the series shifted back to OKC, the Warriors suddenly looked shaken. Game 3 was a 28-point demolition. Game 4 was a masterpiece — Westbrook posted a 36-11-11 triple-double and Oklahoma City won by 24. The league’s smartest, most beautiful offense looked small, rattled and physically overmatched. The Thunder didn’t just look like contenders — they looked like the best team alive.

Up 3–1, the Finals were right there. And then the series turned.

Golden State stopped trying to match OKC’s size and leaned fully into chaos. They went small, spread the floor. They pulled Steven Adams and Enes Kanter into space and dared the Thunder to survive possession after possession of defensive scrambling. The physical advantage disappeared. The pace changed. The margin for error collapsed.

Game 5 was the first warning. Durant and Westbrook combined for 71 points. They also took 61 shots. Westbrook turned the ball over seven times. The bench evaporated. The Warriors survived, because Oklahoma City started playing desperate basketball.

Game 6 is where the story calcified. The Thunder led by eight with six minutes left. The arena could feel the Finals. And then Klay Thompson began hitting shots that defied logic. Contested. Off-balance. From corners that shouldn’t exist. Eleven threes. Every time Oklahoma City landed a punch, Thompson erased it. The noise grew heavier. The possessions got tighter.

And in the final minute and forty seconds, with everything wobbling, the old issues resurfaced all at once. Westbrook turned the ball over repeatedly. Not forced hero passes — handles lost as speed was chosen over control. Jump passes into traffic. The offense stopped moving. The game slipped away.

Game 7 was quieter, but more brutal. Oklahoma City led by thirteen in the first half. They were still right there. But Golden State’s shooting avalanche arrived, the Thunder’s offense stalled into isolations, and the supporting cast disappeared. Westbrook shot 7 for 21. Durant scored but never found rhythm.

That series is ultimately an all-time "What if" for the shape of the NBA's dynasties, organizing principles, and our notion of who represents greatness.

But we’re on this timeline. The one where Kevin Durant leaves a few weeks later, to join the Warriors’ 73-win super team. Russell could have left here too; he was a free agent after all. But, he signed the extension with the Thunder, telling the media, “Loyalty is something I stand by.”

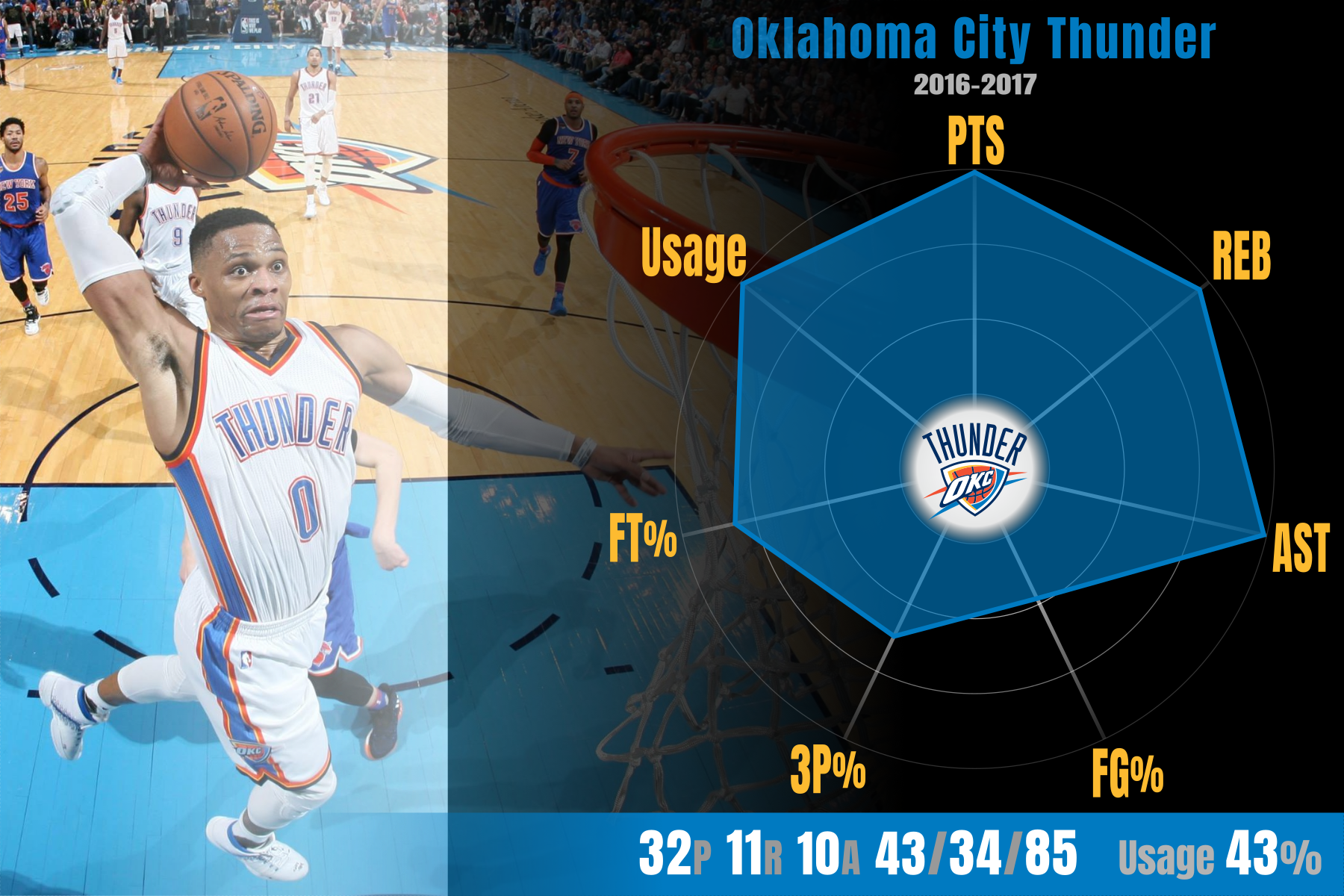

For the 2016-17 season, the Thunder were Russell Westbrook’s team in totality. The roster was a mismatch of timelines. Russ at the peak of his powers, flanked by a handful of veteran journeymen (Nick Collison, Taj Gibson) and bunch of promising talents that were still being developed (Cameron Payne, Steven Adams, Victor Oladipo, Jerami Grant — all in their first three years in the league.)

Every possession began with him, ran through him, or collapsed without him. He didn’t just lead the league in usage. He became the system: tempo, shot creation, emotional current, late-clock salvation.

He averaged a triple double. And as those started to accumulate, it became clear that the single-season triple double record was in reach. The chase past Oscar Robertson’s forty-one became a nightly referendum on whether one player could legitimately carry an entire ecosystem. And the answer kept coming back the same way: game after game, possession after possession, with OKC either tethered to his gravity or lost without it. The defining moment of the season was his magnum opus on April 9th. Triple double number forty-two, while eliminating the Nuggets from a playoff berth, in their house, on 50 points, 16 rebounds, 10 assists, and the walk-off three.

There was a legitimate MVP case for James Harden, who averaged a 29-8-11 with better splits carrying his team to 8 more wins than the Thunder. Came in second, got his MVP the following year.

But this year, “best player on the best team” wasn’t good enough. No, Russ wouldn’t let people look away. The loyal, abandoned hero, still fighting and scrapping for the team that drafted him. Willing a thin roster through games, while having a sense of the moment, and exceeding it in dramatic fashion. And with the advanced metrics indicating that whenever Westbrook sat, the team played at a lottery level? For once, the MVP went to the player who was literally the most valuable to his team.

The postseason ended quickly as James Harden’s Rockets had the last laugh. Westbrook averaged 37 points, 12 rebounds, and 11 assists, one of the highest-scoring playoff triple-doubles in league history. When he was on the floor, Oklahoma City outscored Houston by 3 points per 100 possessions. When he sat, the Rockets outscored them by 60 points per 100 possessions, an insane swing of 63. By that math, to win the series, Russ would need to play 46 minutes per game, never have foul trouble and consistently avoid overtime. The Rockets won in five.

The season’s argument closed exactly where it had begun: not that Westbrook was perfect, but that without him, there was nothing to evaluate at all.

Shortly after the series, Russ sits in his kitchen, unpacks the MVP trophy. It feels weighty in his hand, but at the same time, it feels hollow. The Finals MVP trophy has alluded him, and still there’s no Finals ring yet either. His mind wanders.

He finds himself thinking back to simpler times.

March, 2003. Westbrook Family Living Room, Hawthorne, California.

The TV’s too loud. The box fan rattles. Two GameCube controllers, cords knotted from years of use. The game is NBA Street — versus mode.

While Russ sits in front of the couch on the floor, his friend Khelcey Barrs sprawls across it like he owns the place. Two eighth graders doing eighth grader things.

Barrs scrolls. Timberwolves — Kevin Garnett, Wally Szczerbiak, Troy Hudson. Locks them in.

Russ takes the Sixers. Iverson. Mutombo. Eric Snow — because the game makes you take a third guy.

“Not taking the Lakers?” Barrs says.

Russ doesn’t look up. “They too easy.”

“Yeah. That’s the point.”

The game tips. Iverson crosses over KG and hits a tough step-back over him.

Barrs smiles. “Man, of course it go in. You controlling a league MVP.”

Russ keeps playing. “Still gotta get to the spot.”

They go quiet. Just buttons. Reactions. Small nods when something lands clean.

Russ times a chase-down block. Dikembe puts Wally World's jumper in the fifth row.

Barrs laughs. “You getting serious with this.”

“I been serious.”

A pause.

Barrs says it like it’s obvious. “We enroll at UCLA first.”

Russ nods. “Yeah.”

“Then it's on to the Lakers.”

Russ finally looks up. “One way or another.” He strings together a move. Iverson blow-by. Contact. Finish. He says it without hype. Like a fact. Like a plan. “MVP. That’s gonna be me.”

Barrs studies him for a second longer than the moment needs. “Cool,” he smirks. “But you still losing this game.”

Russ grins and mashes turbo.

Two kids. Two futures spoken like they’re already booked.

May, 2004. Westbrook Family Living Room, Hawthorne, California.

A year later, it’s the same couch. Same TV. Same carpet. One controller on the floor. The other is put away. Tonight, the Laker game is on.

Russ is taller now. Broader. Not a kid anymore, but not finished growing either. He’s sitting forward on the couch, half paying attention to the game, half considering starting his homework for the night.

A knock at the front door. Then the handle. The front door opens. Coach steps inside. He doesn’t smile. That’s the first thing that feels wrong.

Russ looks up immediately. “What’s up?”

Coach takes two steps in and stops. Like he hit an invisible line.

He swallows. “You heard yet?”

Russ shakes his head.

Coach pauses for a second longer than he should. Then says it clean.

“Khelcey collapsed yesterday. At the gym.”

Russ doesn’t move.

“They tried,” Coach adds quickly. “They tried everything.”

The room stays still.

Russ looks at the floor, like he’s searching for something that might have fallen. “How?” he asks.

“Heart,” Coach says. “They said enlarged. They didn’t know.”

Russ stays silent.

Coach keeps going because silence is worse. “He didn’t feel anything. That’s what they said. He was just running a game and then… he went down.”

Russ presses his thumb into the seam of the controller. Hard.

“I know y’all were together every day,” Coach says.

Russ doesn’t answer.

Coach waits. Then adds the only thing he has left. “You don’t gotta be back tomorrow.”

Russ finally looks up. “I’ll be there.”

Coach studies his face for a beat. Sees something there he doesn’t know how to name. He nods once. “Okay.”

Then he leaves. The door closes. For a long moment, Russ doesn’t move. Then he reaches down, picks up the controller, turns it over in his hands. Sees the worn buttons. The smoothed edges. The places where two thumbs used to race.

April 27, 2017. Russel Westbrook’s Kitchen, Edmond, Oklahoma.

Russ sits there alone, a glass of scotch on the table to keep him company.

He isn’t looking at the MVP trophy. He’s looking down now.

Black band around his wrist. White lettering. Two letters and a number that never changed.

KB3

He presses his thumb against it once, like a habit. A check-in.

The thought doesn’t need language. It’s older than language.

The work isn’t done. It never was.

The truth is, there was never going to be a version of Russell Westbrook who learned moderation. There was never going to be a version who learned to pace himself for some imagined future. When Khelcey died, something inside Russ recalibrated permanently. Time stopped feeling like something you could budget. No, he approached every game as if tomorrow is not guaranteed.

He would eventually build his charitable foundation around a phrase — Why Not? — and most people heard it as confidence.

It was never confidence. It was urgency. That urgency built an MVP. It built a decade of durability. It built seasons that bent statistical history out of shape. It also built the volatility. Stubbornness. The nights where the same engine that carried teams also drove them straight into the wall.

You don’t get to separate those things. They’re the same thing.

After the MVP season, the team seemed to backslide — or maybe it just isn't getting stronger as quickly as the rest of the West. Paul George arrives, a two way player with a silky handle and something to prove. The rest of the roster never quite stabilized. One first round flame out. Then another. And finally, the moment that felt inevitable in hindsight: Paul George asks out. The franchise pivots toward the rebuild they'd been quietly laying the groundwork for since Harden left. Westbrook's story arc with the Thunder reaches its natural conclusion.

Presti did right by him. Sent him where he wanted to go. Sent him to chase something that still mattered.

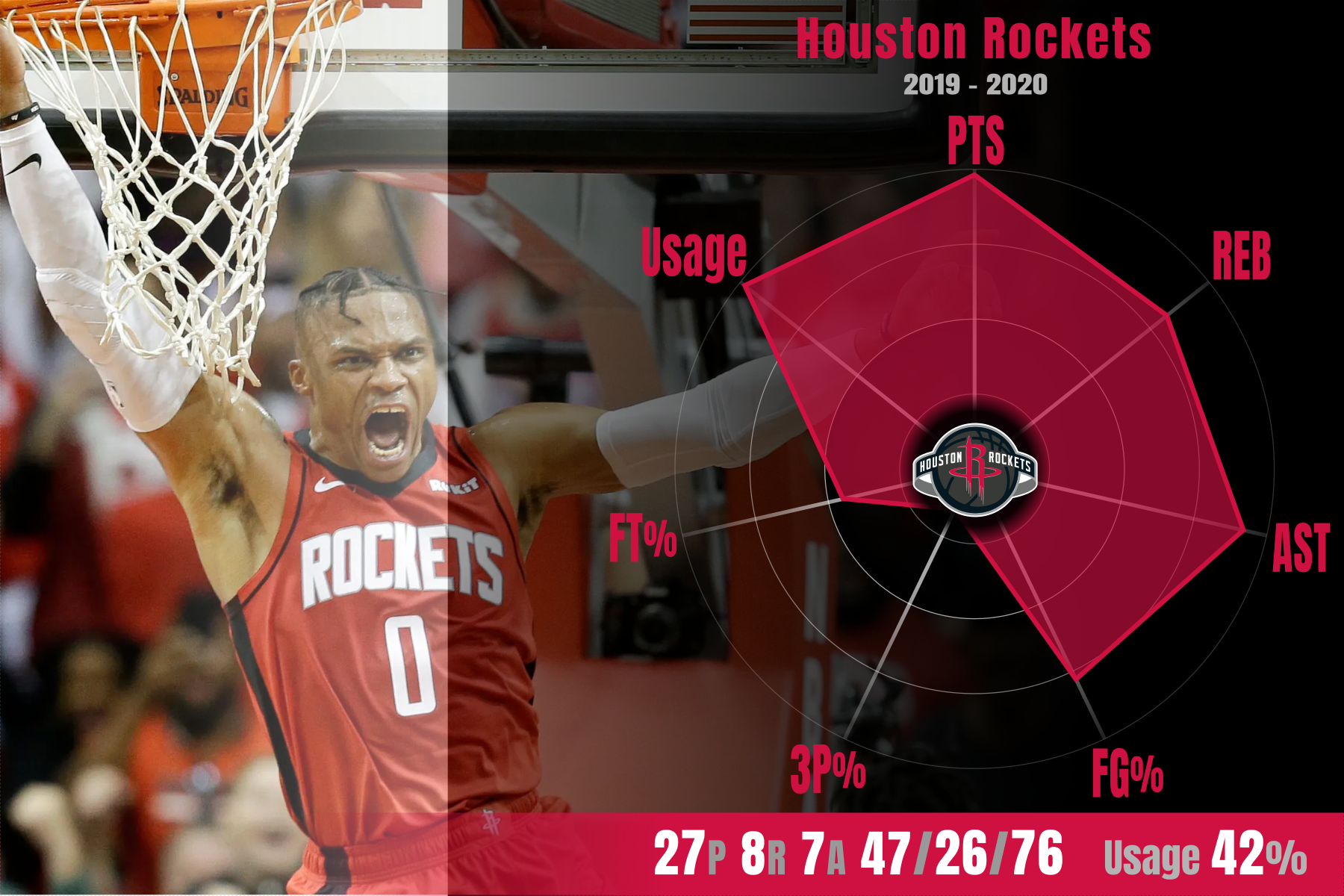

Russell Westbrook was traded to Houston. Reunited with James Harden. For the first time in years, Russell was no longer the focus of the team — he was the gasoline igniting it.

FOURTH DOWN

Still Running

The Houston Rockets had problems to solve. First was a fractured backcourt relationship: James Harden and Chris Paul were no longer speaking, and an ultimatum had been made to leadership to get Chris out of town. The second problem is that, of all coaches, a Mike D'Antoni team had fallen near the bottom of the league in pace as Harden isolation sets chewed up the clock. They wanted to inject speed back into their program. On paper, Russell Westbrook seemed a perfect fit, offering a one-man fast break, and friendly harmony with Harden.

Early in the season, Westbrook tried to play within the existing Rockets template. He took more threes. He avoided the midrange. His efficiency cratered, and defenses responded exactly as expected: they ignored him on the perimeter and crowded the lane. So Houston made the adjustment that defined the season. They traded Clint Capela at the end of January — removed their center entirely — and told Westbrook to learn how to play point-center in the paint.

Quietly, the team also gave Westbrook a directive to abandon the 3-point shot, and a green light to take midrange jumpers — normally a shot that Daryl Morey opposes. But at 23% from the arc and 45% from midrange, the math checked out. Importantly, by stationing him in the paint, he wouldn't be in a position to take a three nearly as often. His attempts from outside dropped from 5 per game to 1.4 after Clint was traded.

On February 6th, the Rockets had had their coming out party for their new offense; the team flew into Los Angeles to take on the Lakers. I distinctly remember watching this game from my hotel room while away at a conference. Despite having an early day ahead of me, I couldn’t turn off the game, couldn’t sleep. The Rockets’ spacing looked infinite, with Westbrook pouring in 41 points attacking straight at LeBron James and Anthony Davis. Any time a perimeter defender sagged off to help on Russ, the kickout to the spacing enforcement team (Covington, Tucker, House, Gordon) was lethal. The team would shoot 45% from outside on 19 makes. It didn’t matter that they couldn’t stop the Lakers’ bigs on the other end. Their shot diet was more rewarding and they took more shots too. I texted Torsten as the Rockets were finishing their 121-111 win, something like “How does anybody stop this?”

For a while, no one did. As the season wound down, it kept working. Westbrook’s efficiency spiked dramatically, jumping from 24 points per game on 43 percent shooting to 33 on 55 percent. Nearly two-thirds of his attempts came within ten feet of the rim. The Rockets looked dangerous.

Then the season stopped.

As basketball eventually resumed in the Orlando bubble, Westbrook remained behind after testing positive for COVID-19. He rejoined the team after two negative tests, but his conditioning had taken a hit, and he reported lingering symptoms. Five days before the playoffs, he strained his quad.

He missed most of the first round against Oklahoma City, scoring just seven points in his return as Houston escaped in seven games. Then came the rematch with the Lakers.

Los Angeles arrived prepared. Frank Vogel benched his traditional centers, moved Davis to the five, and matched Houston’s speed without surrendering length. But the decisive adjustment was simpler. With Westbrook’s burst compromised, the Lakers could trap Harden aggressively and live with the release valve. The pass to Westbrook above the break no longer triggered a downhill punishment. Instead, it produced the shot Los Angeles was conceding. Westbrook’s three-point attempts spiked to 5.2 per game in the series. He converted one in four. Even the midrange deserted him — zero makes on twelve attempts.

The Lakers won in five and went on to claim the championship.

On the flight back to Houston, Mike D’Antoni told the team that he wouldn’t be returning next season, his contract not renewed. Not long after the plane landed, Daryl Morey informed ownership he wouldn’t return either, packing his bags for Philadelphia. Rumors swirled that Harden and KD were looking to reunite in Brooklyn. Westbrook had to be honest with himself — while he certainly didn’t want to be the last man standing after an exodus, sources say he also had expressed unhappiness with standing around to watch 20 seconds of Harden iso ball every set. He demanded a trade, ideally to somewhere he could resume his role as floor general.

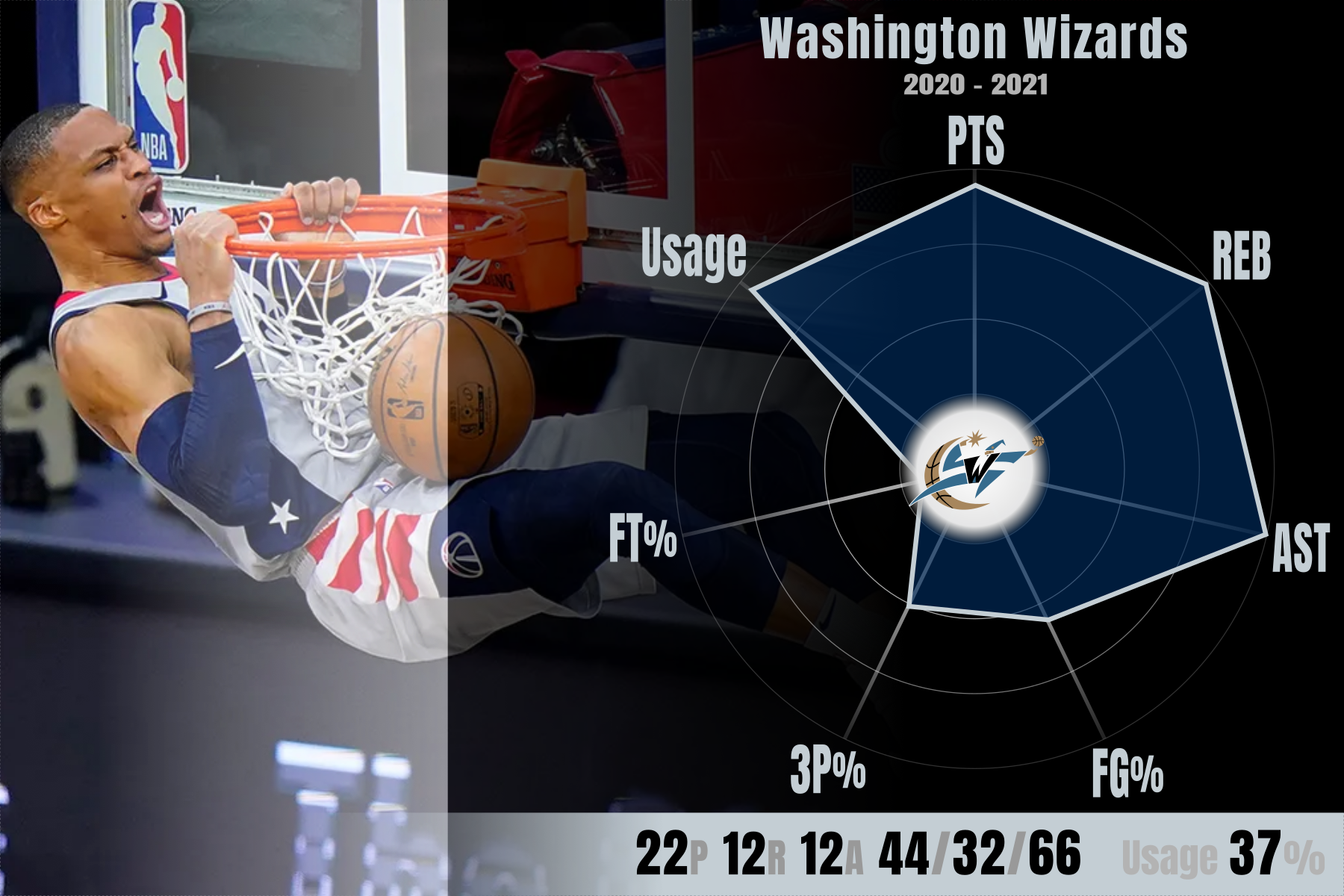

The Washington Wizards had to do something to convince Bradley Beal to flee to greener pastures. His backcourt mate John Wall had been recovering from devastating injuries for two years, and the cycle of playoff-missing mediocrity was long in the tooth. Westbrook offered comparative durability, evidence of all-star level legitimacy just before the bubble, and one more synergy — Scott Brooks was coaching Washington. A chance to skip the normal growing pains of a new addition through familiarity with a coach who never questioned his ability.

Russ was still recovering a torn quad and lingering effects from COVID. Further, he had something to prove, as the pundits had turned on him, throwing the phrase “washed” around. The Wizards too had to disprove their doubters. The roster with no structural identity and had only won 25 games last season.

Naturally, the Wizards stumbled out of the gate, starting 0–5 and sinking to 17–32. The discourse soured. Tanking entered the conversation. Westbrook wasn’t just being criticized — he was being dismissed. Trade him while he still has value, unload the albatross contract.

Then, sometime in late March, the switch flipped.

Westbrook got healthy, and Washington got organized. Not tactically — Scott Brooks’ system was loose at best — but emotionally. Russ and Bradley Beal might not have been hanging out together between games, but they developed a mutual trust. Russ declared his goal to be making Beal the league scoring champ, and he thrived in a role where he’d push the Wizards to the #1 pace in the league, collapse defenses and find Beal in motion for the easy one.

From that point forward, the Wizards played with urgency that bordered on manic. Westbrook averaged a triple-double for the fourth time in his career, but the numbers undersell what actually changed. The listless team found direction behind Russell’s enthusiasm. The Wizards went 17–6 down the stretch, clawing their way from 13th in the East into the Play-In, in a dramatic late-season turnaround.

There were games that felt unreal even by Westbrook standards. Against Indiana in late March, with Beal out, Russ posted 35 points, 14 rebounds, and 21 assists — the first 35/20/10 game in league history — and hit clutch threes over Myles Turner to close it. A month later, against the same Pacers, he recorded 14 points, 21 rebounds, and 24 assists, joining Wilt Chamberlain as the only players ever to produce multiple 20-rebound, 20-assist games.

Russell’s defining game that season came in Atlanta. Westbrook logged nearly every minute, posted another triple-double, and passed Oscar Robertson for the most career triple doubles in NBA history. The Wizards lost by one, but the building rose anyway in recognition. Everyone in the room understood what they were watching — a player emptying the tank because that’s the only way he knows how to play.

Westbrook almost completed his mission to make Beal the scoring leader — Beal finished second behind Steph Curry. Russ led the league in assists (11.7).

In the play-in tournament, they lost to the Celtics in the first game as Jayson Tatum poured in a career-performance 50 point game. The Pacers waited in the next win-or-go-home game. Russ put in 18 points, 8 rebounds and set the table for his whole team with 15 assists on the way to a 142-115 blowout.

There was no miracle run waiting on the other side of the Play-In. Washington lost quickly in the playoffs to the top-seeded Sixers. But the work was done. Westbrook had taken a team that was drifting toward irrelevance and forced it into the postseason.

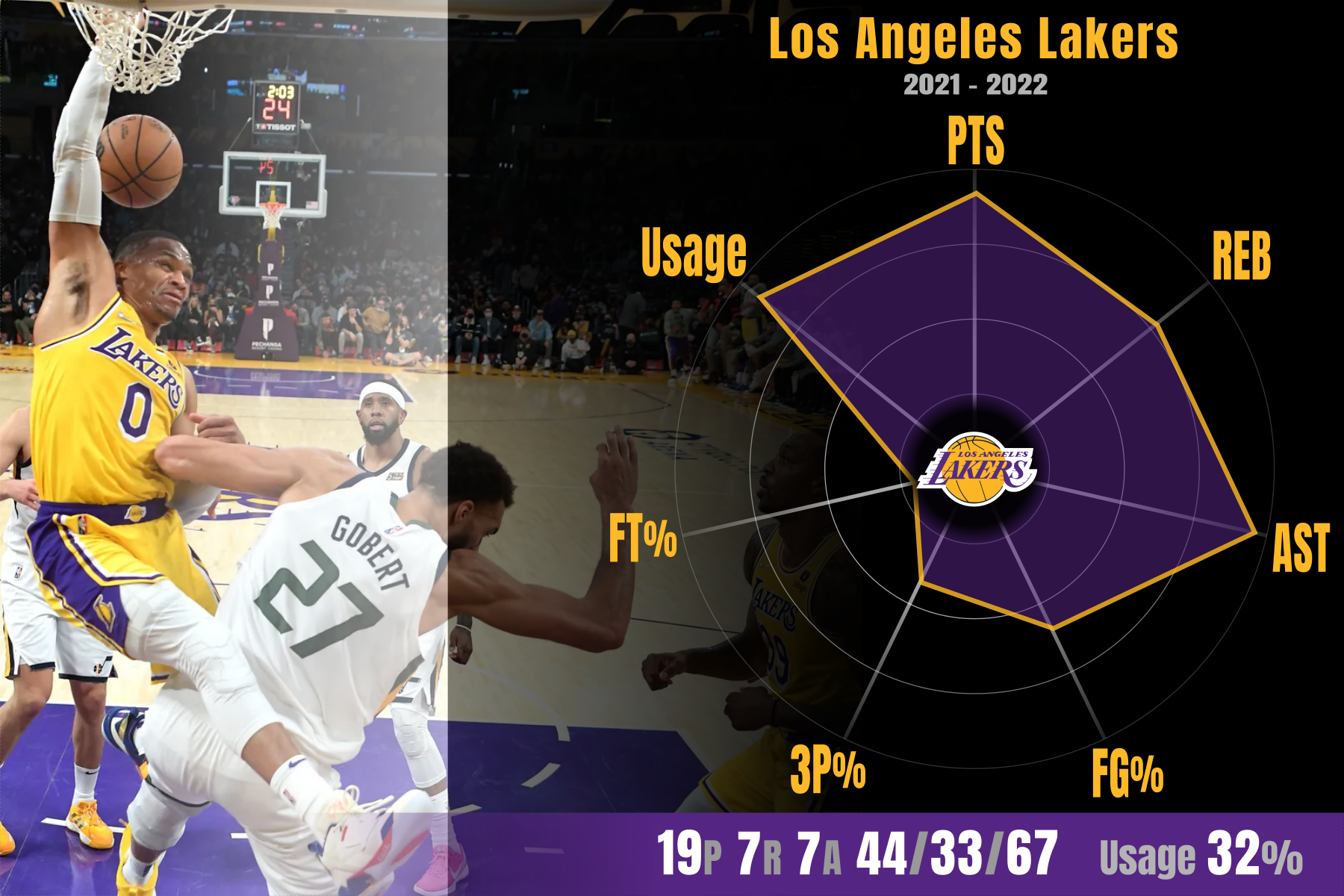

With rumors circulating about Bradley Beal’s patience in Washington running out, Russ began making moves. He met with LeBron James and Anthony Davis at LeBron’s home to talk through what a Lakers fit would look like — including the idea that he’d need to accept a reduced role to make it work. Russ then approached Beal with a bolder concept: ask out together, force the Wizards into a full reset, and let both guys steer their destinations. Beal declined, but he didn’t block Westbrook either — he gave his blessing for Russ to pursue the move. And so it was, after a phone call to Wizards’ brain trust, that Russ was finally homeward bound.

For Frank Vogel, the Lakers’ new Big Three quickly became a big problem. When Anthony Davis and LeBron James shared the floor, Russell Westbrook was often stationed in the corner as a spacer — a role that stripped him of his greatest utility. Defenses treated him as a non-threat away from the ball, sagging off him to clog the paint and daring him to shoot. The Lakers’ offense, designed to operate through LeBron and Davis near the rim, repeatedly collapsed under its own spacing. Lineups featuring all three posted a net rating of –3.5, while lineups without Westbrook performed at a playoff-caliber +6.0.

As losses mounted, the atmosphere curdled. Westbrook became the focal point of fan frustration, and the heckle followed him everywhere: Westbrick. It wasn’t confined to the cheap seats; it became a nightly soundtrack. Westbrook pushed back publicly, drawing a line between criticism of performance and what he felt crossed into disrespect toward his family, particularly his children.

The season wasn’t without moments. In Toronto in March, trailing by three in the closing seconds, Westbrook stripped the ball, sprinted to the corner, and hit a contested three to force overtime. He finished with a 22-point triple-double as the Lakers escaped with a win. And on the frequent nights when LeBron and/or Davis were unavailable, Westbrook showed he could still shoulder the load. Against San Antonio, with LeBron out, he posted 33 points, 10 rebounds, and 8 assists to fuel a comeback victory. He could still carry a team — just not from a third position in the hierarchy.

Two seasons earlier, the Lakers had won a championship in the bubble. This season ended at 33 – 49, outside the playoff picture entirely. Vogel was dismissed and replaced by Darvin Ham.

Ham’s first major decision was to move Westbrook to the bench. Russ agreed, bringing pace and energy to the second unit and briefly surfacing as a Sixth Man of the Year candidate. But the structural issues persisted. The Lakers ranked 26th in three-point shooting, and opponents regularly defended them as if it were five-on-four, sagging off Westbrook to shrink the floor. After twelve games, the Lakers sat at 2 – 10, and the noise only intensified.

Behind the scenes, the picture was more nuanced. Austin Reaves later shared a story from his rookie season that never appeared in a box score. After contracting COVID in Minnesota, Reaves was left alone in a hotel room for a week while the team moved on. He said Westbrook was the only teammate who checked on him daily — calling to see if he needed food, supplies, or simply someone to talk to. Reaves and Max Christie both described Westbrook as a steady presence in a locker room that had grown tense and unforgiving, encouraging them to keep playing their game while the noise swelled. Christie later called him a “high-level professional,” pointing not to speeches, but to diet, routine, and a willingness to explain how to survive in the league day to day.

As the trade deadline approached, the Lakers still hovered below .500 and ultimately brokered a deal that sent Westbrook to the Utah Jazz, who bought out the final year of his contract. After the trade, Los Angeles played at roughly a .600 pace, and the spacing improved. The exit, however, was messy. An ESPN report cited a source describing Westbrook as a “vampire” in the locker room — a characterization that drew immediate pushback from players across the league, including LeBron James, Chris Paul, and Carmelo Anthony. Whatever the basketball failures were, they rejected the idea that Westbrook’s professionalism or intent had been the problem.

It’s fair to ask whether the Lakers erred in allowing LeBron to function in a de facto GM role. Westbrook was not only a poor stylistic fit; he also occupied enormous cap space, earning more than LeBron himself across two seasons. A deal for Buddy Hield — a lower-cost floor spacer — had been available. The Lakers have long earned trust by empowering their stars. In this instance, they may have ceded too much latitude.

The most overlooked aspect of Westbrook’s Lakers tenure was his availability. The Big Three was marketed as a juggernaut, but reality was a revolving injury report. LeBron, Davis, and Westbrook appeared together in just 21 games during their first season. As LeBron (56 games played) and Davis (40 games played) cycled in and out of the lineup, Westbrook remained the constant. He played 78 of 82 games in the first year and 52 more the following season before being traded.

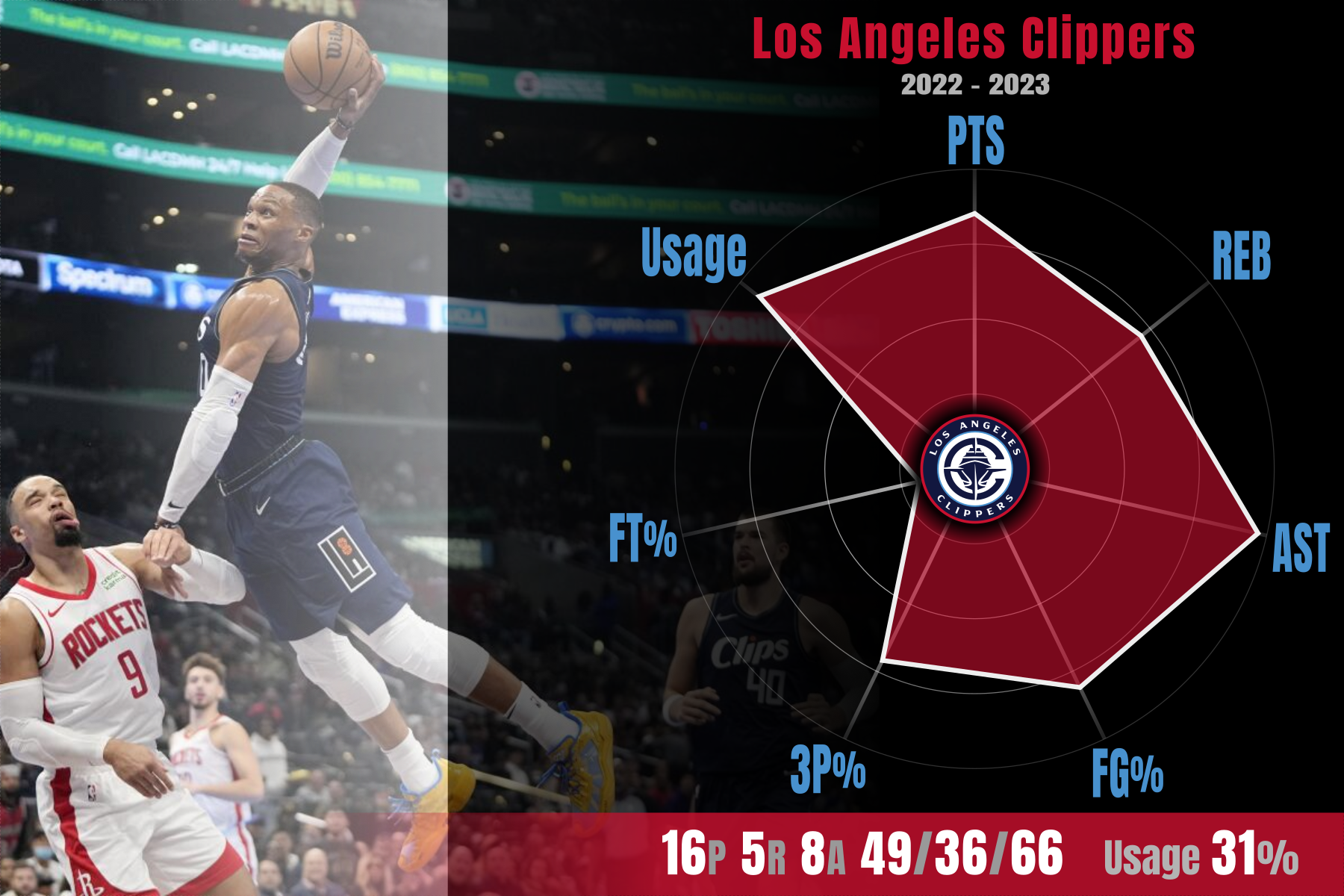

While I publicly broke up with the Clippers last year, in February 2023, when the Clippers signed Russell Westbrook on a veteran minimum deal, the idea of getting production like his at a cost of $4M instead of $44M seemed too good to be true. It was a low-risk flyer on a former MVP.

The Clippers needed somebody like him; they were heavy on talent but light on vocal leadership. Kawhi Leonard led by example, Paul George deferred, and even Ty Lue coached with mild-mannered precision. Westbrook represented a catalyst: he demanded engagement from teammates, talked constantly, and treated regular-season possessions like something that matters.

Ty Lue’s vision for how to get the most out of Westbrook? “We want Russ to be Russ,” he’d explain at the introductory press conference. The adjustments didn’t happen overnight; the Clips lost their next five games.

On March 29, the clippers would visit Memphis, the #1 home record team, currently sitting on a seven-game home win streak. They’d arrive without Paul George (injured) and Kawhi Leonard (late scratch for personal reasons). Most people wrote the game off as an easy loss for LA. Russ didn’t: 36 points, 10 assists, 4 rebounds, and 2 blocks. 13-of-18 shooting, including a perfect 5-of-5 from three. Relentless control, pick and roll surgery, and lethal shooting to punish the defense for cheating off of him. He could still carry a team. The team would go 11 - 5 to close out the season as the 5th seed.

In the first round of the 2023 playoffs against the Phoenix Suns, the Clippers’ stars disappeared. Leonard played two games. George played none. What remained was Westbrook, alone against Kevin Durant, Devin Booker, and Chris Paul. He played nearly 39 minutes a night, defended like his life depended on it, and absorbed usage because there was no one else to absorb it.

Game 1 said everything. He shot 3-for-19 — and still won the game, sealing it with a late block on Booker and the presence of mind to throw the ball off him out of bounds. Over the next three games, he scored 28, 30, and 37 points. The efficiency wavered. The effort didn’t. By the time the series ended, Westbrook had posted 23.6 points, 7.6 rebounds, and 7.4 assists per game, keeping the Clippers competitive in a series that should have ended quickly.

That willingness to adapt showed up again the following season. After the Clippers traded for James Harden, the team promptly lost six straight games. The roles were muddy. The offense stalled. And then Westbrook did something almost unheard of for a former MVP: he volunteered to come off the bench. No public standoff. No sulking. He framed it simply — whatever helped the team win.

Westbrook became an energy engine for second units, crashing the glass, defending multiple positions, and injecting life into games that had started to drift. The team stabilized, and Russ’s impact was felt in tempo, in deflections, in the way young players gravitated toward him on the bench. Terance Mann talked about Westbrook coaching him through entire stretches without sitting down. Bones Hyland and Kobe Brown were often at his side, listening.

The Clippers improved from 44 wins to 51, entering the playoffs as the 4th seed, facing off against the Dallas Mavericks. The Clippers were deeper and healthier than last year. And yet, this is where my fan enthusiasm for Westbrook had to be taught a lesson.

Dallas ignored him on the perimeter, crowded the paint, and waited. The shots didn’t fall. The burst wasn’t there. He averaged 6.3 points on 26 percent shooting for the series, struggled from the line, and had a night where frustration spilled into an ejection before he had scored a single point. The team needed him to just fit into a modest role in the system, and when it started going wrong, Russ tried to force it to improve. You could see his decision making deteriorate in real time.

The Clippers years clarified what Russ still is — a player whose value explodes when responsibility and flexibility are required, especially when the price is right. On a minimum deal, with flexible expectations and a real bench role, he was a feature. But when the roster became deeper, healthier, and the rotation was more crowded, he struggles to fit his game into a reduced role.

As a fan, the contrast was jarring. How was it that the very traits that made him a bargain at four million made him a liability at fifty-one wins?

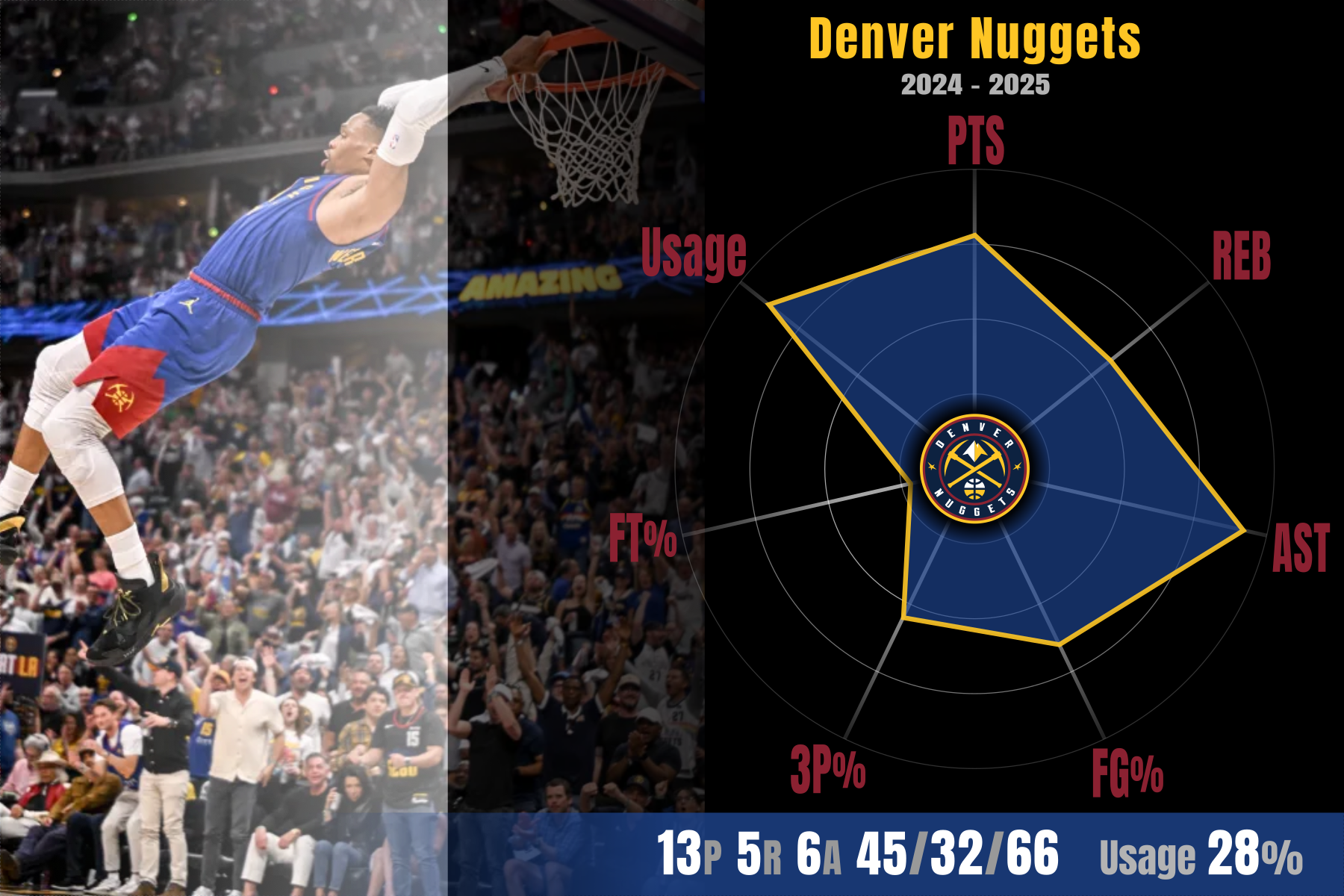

Denver was not supposed to be a referendum. When the Denver Nuggets signed Russell Westbrook to a veteran minimum deal in the summer of 2024, they had just moved on from Reggie Jackson, paying draft capital to dump his salary. Since their championship, the team had appeared at times to have gotten bored, and leadership wanted a floor general who was more vocal and demanding. The idea for Westbrook’s role was modest, specific: lead the bench, inject pace, keep the offense functional when Nikola Jokic sat. That plan didn’t survive the season.

As injuries accumulated — concussions, hamstrings, illnesses — Westbrook became something else entirely. Jamal Murray missed time. Jokic missed time. And quietly, Westbrook started 36 games, more than he had in years.

When Jokic and Russ shared the floor, Coach Malone emphasized Westbrook's movement off the ball — hard cuts, early seals, and purposeful corner spacing — while trusting Westbrook to attack only when the advantage was tangible.

The pairing worked, posting an elite net rating, and for long stretches the offense barely missed a beat.

When the stars were out entirely, Westbrook reverted to muscle memory.

There was the night in Golden State, with Jokic and Murray sidelined, when he logged a 12-point, 16-assist, 11-rebound performance that turned a scheduled loss into a controlled upset. He hit a late three, organized the floor, and dragged the game into relevance through sheer involvement. Earlier in the year, against an undefeated Oklahoma City team, he looked briefly unbound by time — 29 points, constant pressure, the kind of game that steadied a drifting locker room. Denver didn’t wave the white flag when stars sat. Westbrook wouldn’t allow it.

The regular season told a clear story. He played 75 games — more than Murray or Aaron Gordon — and when asked to start, the Nuggets won at a pace that surprised even them.

Off the floor, the impact landed where Denver actually needed it. Jokic leads by example, not volume. Murray is internal. Westbrook filled the gap. Younger players gravitated toward him. Peyton Watson, a fellow Southern California native, leaned on him publicly and privately, crediting Westbrook with teaching him how to survive the G-League grind and hold himself accountable on defense. Christian Braun thrived in transition as Westbrook pushed tempo relentlessly. Practices got louder. Rotations got called out.

Against the Los Angeles Clippers in the first round, Westbrook was indispensable. He closed games. He pressured ball handlers. In Game 7, he finished with 16 points, five assists, and five steals, playing through pain that wasn’t yet public. Denver advanced, battered but intact.

Against the Oklahoma City Thunder in the second round, the cost finally surfaced. It emerged after the season that Westbrook had been playing with two breaks in his shooting hand. His efficiency collapsed. The Thunder sagged off him, clogged lanes, and forced Jokic into crowds. Over the final games of the series, Westbrook scored sparingly, his plus-minus cratered, and the Nuggets ran out of answers. He never asked out. He never sat.

That refusal sits at the heart of the Denver chapter, unresolved by design. From one angle, it’s stubbornness — minutes taken while spacing evaporated. From another, it’s exactly why Denver wanted him in the first place. They had cleared the bench. They had traded away their safety net. When the roster thinned and the season tilted, Westbrook was the one still standing, playing through damage so the team didn’t have to improvise under fire.

He opted out that summer, leaving behind a season that resists a clean label. He earned more on a new contract than on his player option, but he probably moved on from Denver because they wanted to prioritize developing their younger backcourt; Christan Braun, Spencer Jones, and the like.

I wonder if the Nuggets wouldn’t have been better off benching Russell’s broken hand in the second round. But I suspect that if this was what Jokic and Malone really wanted, it would have happened. No, they decided to stay with the variance and see where it took them.

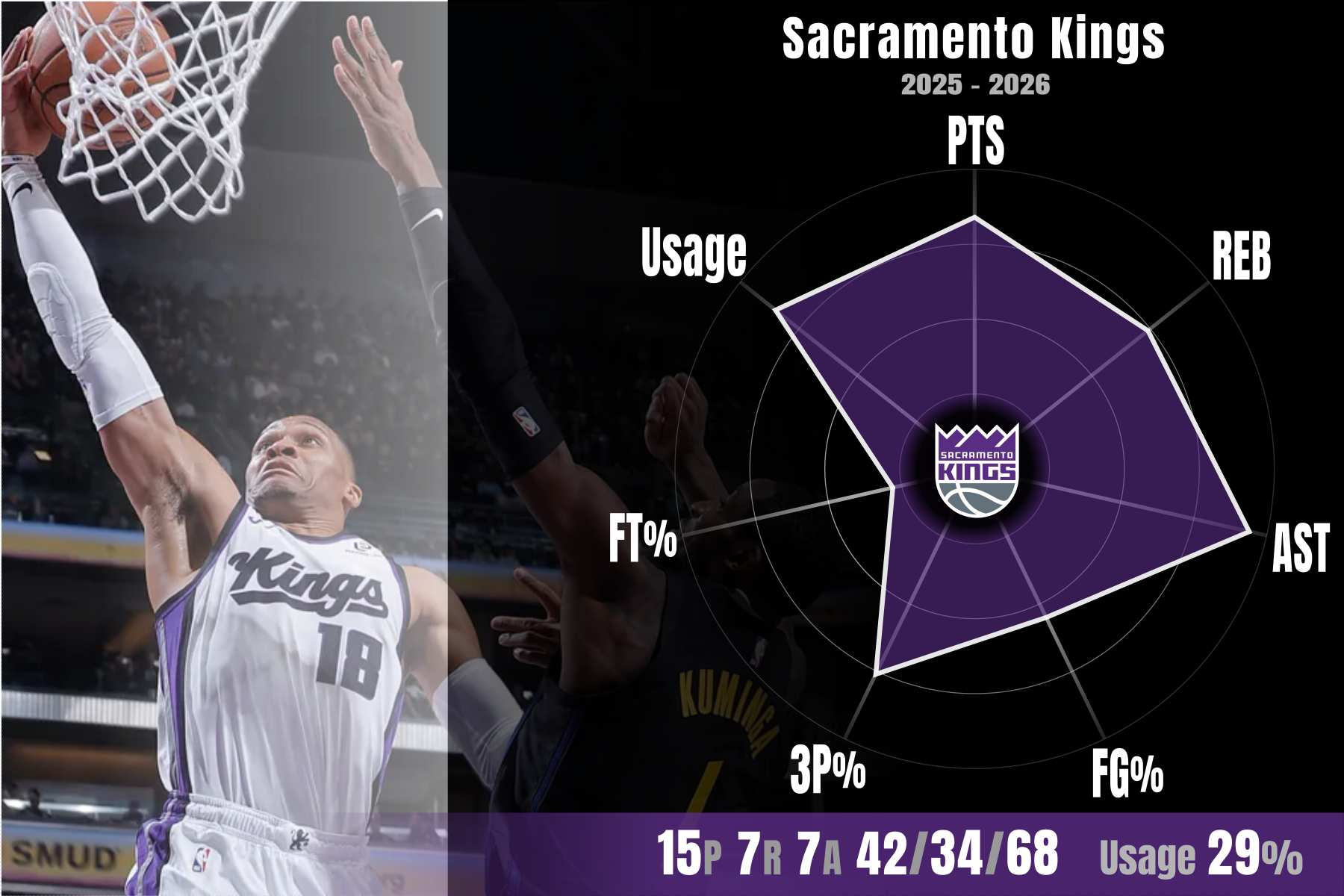

Russell Westbrook did not arrive in Sacramento to fix a contender. He arrived because there was no one else left to run the team.

By the start of the 2025–26 season, the Sacramento Kings were in visible free fall. They’d gone 40–42 the year before, missed the playoffs, and then detonated their own stability by firing Mike Brown, the coach who had ended a 17-year postseason drought. The move fractured the locker room. Franchise star De’Aaron Fox forced his way out in protest, landing in San Antonio and leaving the Kings without a point guard, a direction, or much goodwill from their fan base.

Westbrook was signed in October on a veteran minimum deal because Sacramento needed a pulse. Preferably one that showed up every night.

He did — immediately.

Just months removed from surgery to repair two fractures he’d played through in Denver’s playoff run, Westbrook was back on the floor for the home opener. He became their most available player, logging over 32 minutes a night by January, despite being 37 years old. The pace was relentless. The tone intense. The wins? Sporadic.

But at least the nights weren’t empty. On January 2, 2026, against the Phoenix Suns, Westbrook passed Oscar Robertson to become the highest-scoring point guard in NBA history. The Kings lost, but Westbrook was the only player with a positive on-court impact, attacking with a controlled edge that suggested the milestone mattered less than the act of taking responsibility again. Two weeks later, against Washington, he put up 26 points on 9-of-14 shooting and hit six threes — his best shooting night of the season — quietly undercutting the idea that spacing had permanently abandoned him.

By midseason, Westbrook was leading the Kings in assists, rebounds, and made three-pointers, and sitting second in scoring. Not because it was efficient roster design. Because someone had to.

The most consequential work, though, happened earlier in the day. With Fox gone, Sacramento’s future tilted toward its youngest players, especially rookie center Maxime Raynaud. Westbrook latched on immediately. Practices turned instructional. Games turned simple. Raynaud ran harder, sealed deeper, and caught the ball where it was easiest to finish. Local reporting credited Westbrook with “gift-wrapping” Raynaud’s production — pocket passes, early lobs, constant direction. In the treatment room at 9 a.m., Westbrook set the volume before the coaches arrived, chirping at rookies to get moving, to get loose, to treat a lost season like a professional obligation instead of an excuse.

Look, there’s no playoff story here. No redemption series waiting around the corner. What Sacramento offers instead is something starker: a team that lost its star, its coach, and its sense of self — and found itself orbiting a 37-year-old guard playing heavy minutes after hand surgery because somebody had to stabilize the floor.

The Kings still control their 2026 draft picks. Westbrook’s effort actually hurts the team’s draft chances. Russ probably hasn’t even considered this; showing Keegan and Maxime what hard work and sacrifice look like in January is far more valuable to him than a few extra lottery ping pong balls in May.

We began this piece looking at Russell Westbrook through the lens of his early dreams of being a football star. If we’ve learned anything on this journey, it’s that there is one skill that Russ never did learn from football: when to punt.

And on that note, it’s time to take stock of our journey.

The Signal in the Noise

Here’s the thing about Russell Westbrook: he raises the floor everywhere he goes. Bad teams stop drifting. Young teams grow teeth. Fragile teams find they can stabilize despite one or two key players missing time. That part isn’t really up for debate anymore.

Ceilings are trickier.

If a team already has someone who can calmly author the game when it tightens — someone whose decision-making shrinks instead of splays under pressure — Russ won’t raise that ceiling. He might even rattle it. Washington worked because there was no ceiling to disrupt. Sacramento works because there’s barely a roof. The Lakers didn’t because there absolutely was.

I’ve also come to believe that Russ is at his best when he’s setting the table for a gifted scorer who doesn’t need to dominate the ball to matter. The Durant Thunder made sense. Russ bent the defense, KD finished the sentence. That version always felt lighter than the Westbrook Thunder, where Russ had to be the sentence. Same with Sacramento now — heroic, but exhausting. That’s not a character flaw. It’s a usage note. Ball dominant scorers are a more challenging fit; LeBron and Harden eventually required Westbrook to be moved to the second unit. Russ would have excelled in roles like that of Jason Terry on the Nowitzki Mavericks or Eric Snow on Kevin Garnett’s Timberwolves. Modern stars like Giannis and Wemby would have played well with him too I suspect.

What Russ is not — and never has been — is restrained. And you wouldn’t want him to be. When teams tried to sand him down, to make him quieter or more theoretical, the result wasn’t efficiency. It was paralysis. Just ask the Lakers. A muted version of Russell Westbrook isn’t a compromise — it’s a malfunction.

That same wiring explains the durability. Hard work. A gifted physique. And a worldview that treats today as the only day that’s actually promised. That combination produces an iron-man mindset. It’s why he plays through broken hands. It’s why he shows up when others don’t. It’s also why the wear eventually shows.

It may be that his cleanest role was always as a second-unit anchor. Not because he lacks ambition, but because if Russell Westbrook is your closer, the variance becomes existential. He will make the decision. He will live with it. And so will you.

Russ is going to be Russ. He’s a man with principles. That makes him legible. It also makes him solvable. The league figured out the equation years ago: dare him to shoot, bait him into hero ball, let the math do the rest. He has main-character energy — of course he thinks the shooting contest with Dame is destiny.

The Ink Blot Test

Let’s be honest about something first. There are things about Russell Westbrook that are easy to admire, if you’re willing to look at the whole person instead of the shot chart.

He’s a family man. He’s only ever had one wife. He’s fiercely protective of his kids. He doesn’t posture about it, doesn’t sell it, doesn’t use it as branding. He just lives that way. In a league where personal messiness regularly spills into public view, Russ has kept his private life private — not because he’s hiding anything, but because it actually matters to him.

He has integrity. Not the convenient kind. The inconvenient kind. The kind that doesn’t bend when it would clearly be easier to do so.

He’s a leader — not a vibes guy, not a press-conference leader, but the exhausting, everyday version. The one who shows up early, talks constantly, and refuses to let the room go flat. He’s a natural mentor and a natural teacher, which is rarer in this league than we like to admit. Nothing in his contract says he needs to do these things. He feels obligated to.

He wears his heart on his sleeve. Every minute. Not just the fourth quarter. Not just nationally televised games. October counts. January counts. Tuesday nights in bad arenas count. He wants the win tonight, not just the idea of a championship someday. He gives a damn — loudly, visibly, sometimes uncomfortably.

And yes, he cares too much to sit if he thinks he can play. That’s not branding. That’s belief. Russ genuinely thinks there’s value in leading by example every time. He doesn’t see toughness as something you toggle. If you load manage sometimes and gut it out other times, are you really tough? In his mind, probably not.

And here’s the hard truth: If Russell Westbrook were willing to live in gray areas, he probably would’ve had a more “effective” career by modern standards. Fewer minutes. Fewer collisions. More preservation. Better efficiency. Longer shelf life.

But that wouldn’t be Russell Westbrook.

And that’s the ink blot test.

The casual basketball fan will tell you why they’ve drifted from the league: Players feel entitled. They care more about their bag than the building. They change teams at the first sign of adversity. They don’t seem invested. Load management is the proof. The effort feels conditional. The players don’t care the way the fans do.

That same fan will often tell you Russ is washed. A loser. A net negative. Inefficient. A ball-hog.

Those two takes don’t reconcile.

Because if what you miss is effort, presence, accountability, and someone who actually treats every game like it matters — Russ is the antidote. He plays too much. He cares too much. He ruins lottery odds. He refuses to read the room.

When you watch Russell Westbrook, what you see says less about him than it does about what you value.

If you prize control, optimization, and clean outcomes, he will drive you insane.

If you value effort, integrity, and the idea that competition is something you honor daily, not strategically, he makes uncomfortable sense.

Because Russ hasn’t changed. Not much.

The league has. The incentives have. The patience certainly has.

When he’s gone — when there’s one fewer guy who actually cares this much — I think we’re going to miss him more than we expect.

Not because he was perfect.

But because he was real.

Todd / 120 Proof Ball

If you liked this piece, you’re part of the problem.