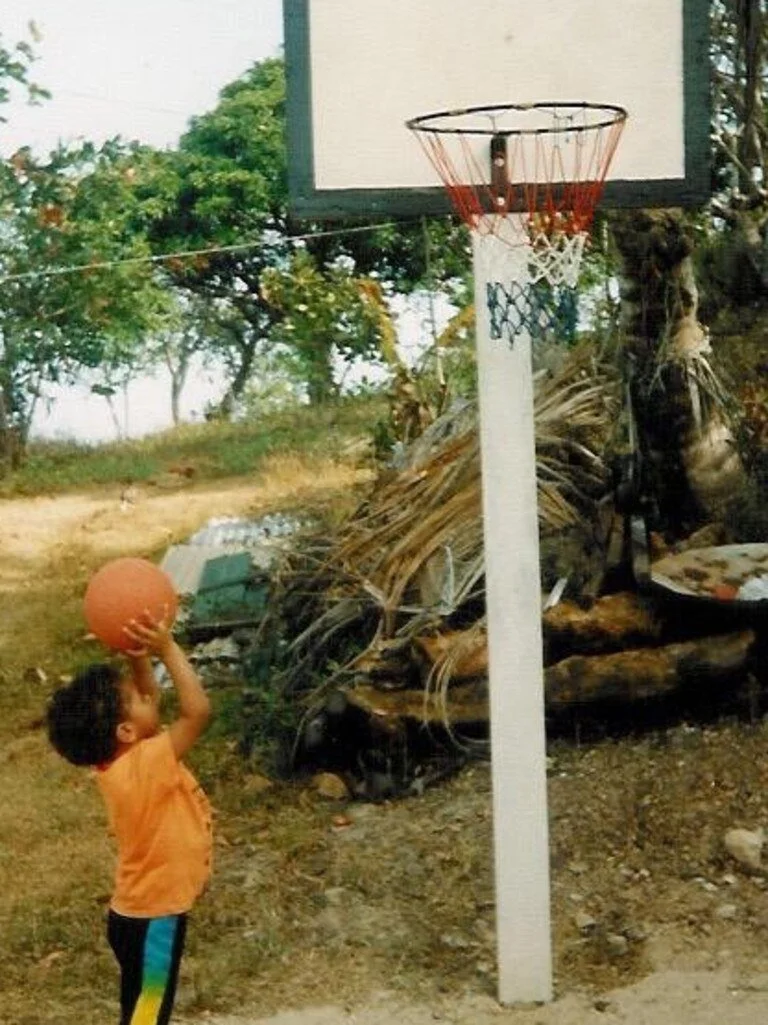

The Hoop Ain’t Much, But It’s Ours

You don’t need a court for basketball — just something to throw, something to throw at, and the will to chase every miss.

Ikebukuro, Tokyo

There’s a hoop bolted to a balcony three floors up from a gravel path in Ikebukuro. There’s barely room to park a Prius in front of it.

I imagine the local kid who calls this homecourt. Let’s call him Kenji. The ball arcs high, kisses the railing, and clatters onto the neighbor’s balcony for the sixth time this month.

Slippers shuffle; a tired father bows, retrieves, returns.

Kenji thinks he’s Steph, but he’s Carlton. And maybe that’s the point.

Because basketball, for the rest of us, isn’t played under lights. It’s wedged between parked cars, over laundry lines, beside vending machines and convenience-store walls. It’s every missed shot you chase down because no one’s keeping score.

Long Grove, Illinois

Growing up in Illinois, my home hoop was mounted above the garage door at the top of a driveway that must have found the only incline in that whole flatland of a state.

While I was still learning how to manage limbs longer than they had any right to be, my practice sessions out front were basically orchestrated by Tom Thibodeau.

Lay-up? Two points.

Swish the ten-footer? Count it.

Brick it off the rim? Sprint downhill before a passing car claims the rebound, then Stair-Master my way back up, winded and slightly humbler.

Every player has their own flawed court. Some tilt downhill, some rattle, some demand penance for every miss.

In Harlem, they built the kind that bite back.

Harlem, New York City

At St. Nicholas Park, the old steel rims absorb missed shots with an angry clank, sending the ball careening upward and the backboard into a rickety seizure.

Players learn fast, adapt. Either learn to drive, or learn to put your shots in clean.

“These are ghetto rims,” said Quaeshawn Berry, a 14-year-old regular. “But I prefer these. I’ve been playing on these my whole life.”

Each rim was forged by hand — shaped by city blacksmiths who still hammer steel the way they did a century ago. They built thousands of them, each slightly different, each one punishing in its own way.

Those rims made Harlem’s players into realists. Every clang a sermon: don’t trust touch, trust will.

Where Harlem’s game was hammered from steel, another version was growing half a world away — not on blacktop, but on earth itself.

Canberra, Australia

In the Australian outback, the court isn’t concrete; it’s red dirt and stubborn grass. The ball barely bounces, so dribbling dies quick. What replaces it is teamwork — cuts, passes, trust.

Patty Mills grew up in that geometry, on cracked surfaces and community courts that turned into meeting grounds. He’d later found Indigenous Basketball Australia, creating leagues for kids whose first baskets were nailed to fenceposts.

Grass basketball teaches a different gospel. You don’t perfect control; you abandon it. You stop dribbling and start reading. You learn to move together or not at all.

Where the ground won’t give you a bounce, you learn to create one in each other.

Whether it’s steel, soil, or sand, the game survives the surface. But sometimes, it has to survive having no hoop at all.

Borough Park, Brooklyn

In Borough Park, the hoop wasn’t a rim. It was a plastic milk crate, bottom cut out, tied to an archway with bungee cords. Every errant shot ricocheted into the alley, every possession paused for retrieval.

But the kids didn’t mind. “We’re just happy to play,” one said, proud as any All-Star.

A hundred and thirty years after James Naismith nailed a peach basket to a gym wall, kids on 15th Avenue were still doing the same thing — making a game out of what they had, not what they were given.

They didn’t wait for the city to build a gym. They didn’t even ask.

If you build it, they will come. If you don’t, they’ll come with a milk crate and bungee cables.

Steel builds will. Dirt builds trust. Inclines fix your mechanics — or your conditioning. Milk crates prove that perfect is the enemy of good enough. Every court rewrites the game — and rewrites the kid playing it.

Kenji shooting over a balcony rail isn’t different from Mills weaving through red dirt or those kids in Borough Park aiming at a crate. They’re answering the same invitation — the one the game whispers to all of us.

Nobody made me, or Patty Mills, or those kids in Borough Park go out there and shoot. Nobody told us to call friends for three-on-three, or to chase the ball when it rolled downhill, or to tape a hoop together from scraps.

The game wants to be played.

The spirit of play calls us — same voice, different accents, heard from Tokyo to Illinois to New York.

And we answer.

Todd / 120 Proof Ball

If you liked this piece, you’re part of the problem.