Those Who Would Run the World

Paul Terrell pinched the bridge of his nose, the way men do when they’re about to wager more than they can explain. The Byte Shop was his life’s work—transistor bins, spare boards, the occasional dreamer wandering in for a soldering iron, the air thick with the burn of fresh circuits.

Across from him sat another dreamer. This one smiling like he already knew the ending.

Jobs leaned forward. “Five hundred per unit,” he said softly, “and you’ve got a deal.”

Terrell hesitated—just long enough for the dust motes in the garage air to hang, suspended, like they were listening too.

“All right,” he said finally. “You got ninety days.”

Jobs didn’t blink. “I’ll have it in sixty.”

And that was it. The handshake. Two men stepping into a future only one could see through the haze.

Terrell left. The door closed with a soft click that sounded, in the sudden quiet, like a starting gun.

Steve Jobs—twenty-one, broke, ambitious, runway gone—turned to Wozniak with the stunned half-grin of a man who’d either saved the company or doomed it.

The garage smelled of solder and desperation.

Because the truth was brutal and simple:

He hadn’t built fifty computers. Hadn’t finished one that was truly ready for shelves. No parts stacked in neat rows. No credit left to beg. No safety net, no fallback, no plan beyond the calendar pages burning one by one.

Just sixty days, one prototype humming faintly on plywood, and a belief so raw it verged on madness.

That same madness has always powered the ones who refuse to wait for permission.

The ones who would run the world.

The Madness of the Innovator

There’s an audacity to looking at the way things have always been done, and concluding that your own approach is strictly better. Every revolution begins with someone who sees those gaps — the opportunities hiding in the blind spots — and decides to jump before the bridge is built.

Whether you’re running a company or a pro sports team, innovation requires a little genius and a dangerous amount of delusion. A willingness to declare the future before anyone else believes in it. A belief that if you run fast enough, the ground will appear under your feet. But belief alone isn’t enough.

To build something new — truly new — an innovator must wrestle three enemies at once:

Time: A runway that’s always shorter than it looks. A countdown that creates as many unforced errors as it exposes. Contracts expire, windows close, your people won’t stay young and healthy forever.

Team: People who want to believe, but who also need evidence. Talent that gets tired. Morale that cracks under the weight of unproven vision. Victory has a hundred fathers; failure is an orphan. When the results dip and the noise grows, how do you keep your people from jumping ship to someone else’s dream?

Backers: Investors, owners, boards, management — all of them quietly doing math. The kind that rewards predictability, punishes variance, and tilts heavily toward the safe bet. They’ll cheer boldness while the graphs point up, but the moment the numbers wobble, they start whispering about pivots, controls, and contingency plans. Backers don’t need to fire you to kill your vision. They just need to stop believing.

If one of these collapses, the entire vision goes with it. That’s the innovator’s madness — knowing the system could break at any moment and running faster anyway. It is a miracle that any company survives this gauntlet. It’s even rarer that any team does.

The Formula

And yet—if you zoom out across the last fifty years—something remarkable emerges. A pattern. A rhyme. The origin story of every company that changed the world looks strangely familiar: a fast break to beat the buzzer. A sprint to build before the competition wakes up, outrun imitators, and get results on the board before the skeptics tear the idea apart. One mad push to prove the concept before a cleverer one takes its place.

For companies that dominate, speed isn’t a tactic. It’s the business model.

And the NBA’s great innovators—those who dared to rewrite how the game could be played—were cut from the same cloth. In a league where second place is the first loser, the ones who tear up the old playbook and sketch a new one on the fly inevitably echo the giants of business.

The parallels aren’t loose. They’re structural. They’re often uncanny. And the more you look, the more the teams begin to match their corporate counterparts — one to one, belief to belief, flaw to flaw, miracle to miracle.

APPLE → Phoenix Suns (2004–2007)

“It just works” isn’t a slogan; it’s an ethos — beauty by design, intuitive seamlessness. Apple products don’t need manuals because the system itself teaches you how to use it. You swipe, it responds. You tap, it reveals. D’Antoni believed the same thing about basketball. Calling set plays only added friction. Every possession was built to strip away delay. No holding, no hesitation — trust the flow.

That flow came from the ecosystem. Apple’s power is that every device amplifies the others. The Suns operated the same way: every player understood the optionality of their role inside each possession, so the ball didn’t need directions. It found the best shot because the system cleared the path for it.

Apple’s real genius isn’t marketing — it’s precision engineering. They obsess over processor efficiency, battery life, thermal design, form factor, weight. They win by shaping function into elegance. Phoenix did the same with possessions. They engineered pace and optimized efficiency until Suns basketball made half-court offense feel like a frictionless touchscreen: responsive, adaptive, accelerated.

Steve Jobs wanted users to see themselves in their iPhones — literally. He insisted the screen remain reflective until the moment it lit up. D’Antoni’s system carried the same philosophy. It didn’t impose identity or restrict players. It revealed who they were, and what they could become when the game was allowed to breathe.

AMAZON → Houston Rockets (2016–2020)

Pace-by-math. Margins-as-weapon. Amazon didn’t conquer retail with charm — they conquered it with volume. Prime two-day shipping rewired consumer expectations, and the moment competitors finally caught up, Amazon cut the clock again: Next-Day. More packages. More planes. More fulfillment centers. More data. More speed. A logistical avalanche engineered to suffocate anything built on slower, older assumptions.

Houston was that same machine, tuned for basketball instead of boxes. Daryl Morey asked the coldest possible question: “How do we weaponize efficiency?” His answer was a supply chain of points — threes, free throws, rim attempts — repeated at industrial scale. More pace. More possessions. More math. Less midrange. Less romance. Beauty optional; efficiency mandatory.

And like Amazon’s retail blitz, it worked. The Rockets produced blowouts that felt algorithmic, games where opponents looked obsolete from the opening tip. Harden isolations, 5-out spacing, and a shot profile shaved to the bone weren’t always pretty, but they overwhelmed you the way brick-and-mortar stores were overwhelmed in 1999.

Both systems exposed the same truth: If you can make the margins your weapon, the game stops being fair.

NETFLIX → Sacramento Kings (2001–2004)

Why fight for a share of an existing category when you can invent one no one else is competing in and dominate the empty field before anyone realizes it exists? Even in the red-envelope era, Netflix was already offering consumers something Blockbuster never could: less friction. Each rental meant two fewer trips to the store, late fees vanished, and the whole experience felt like a small miracle when compared to asking a bored teenager whether you should rent Vanilla Sky or The Piano Teacher. But the real party piece was convincing the world that we’d switch to streaming, at a time when we were still dialing up on 56K.

The early-2000s Kings were the basketball counterpart to that impulse. They built a style the league had no framework for: five-man passing as identity, high-post orchestration as engine, motion without ego, aesthetics as competitive edge, and democratic decision-making in an age still moving at the pace of The Mailman. They stripped the friction out of half-court basketball; each man had two seconds to score or pass. Decision-making accelerated into the digital age.

Netflix created its category outright. Sacramento created its style outright. Both did it the same way: a feast for the eyes, delivered fast. The proof came later, when the 2014 Spurs, the Warriors dynasty, and the modern Nuggets all wove pieces of Sacramento’s blueprint into their own championship DNA.

The Kings didn’t just play differently. They previewed the next decade.

TESLA / SPACEX → We Believe Warriors + Early Curry Warriors

Tesla wasn’t the first mover on electric vehicles — their kung fu was to make EV’s sexy. They partnered with Lotus Engineering to build a chassis out of aluminum and space-age adhesives, to offset the weight of adding batteries to a car. The result: a Tesla Roadster that got compared against Porche’s rather than Prius’s.

SpaceX didn’t sell rockets — they sold spectacle, televised in real time, audiences glued to screens to see if they could achieve greatness or fail spectacularly. In February, 2018, SpaceX would test the payload launch capabilities of their Falcon Heavy rocket. Upon arriving in orbit, they launched a single Tesla Roadster, with a mannequin in a spacesuit as “driver” and sent it into an orbit that takes it out beyond Mars and back towards the sun.

Before ever proving that SpaceX or Tesla could be winning, profitable enterprises they had succeeded in capturing imaginations.

So did the We Believe Warriors. Baron Davis dunking on Kirilenko was the basketball equivalent of a Falcon 9 landing upright on a barge. Impossible, stunning, physics-defying, myth-making. And the early Curry Warriors (2013–14) were no less audacious. A skinny point guard defying any larger defender to stay close enough, a roster built around joy, and a style that offended traditionalists.

When you’re a small market team, the real value of capturing a rabid fanbase is that your small market can suddenly spend on the team like they’re the Knicks. Weakness becomes strength.

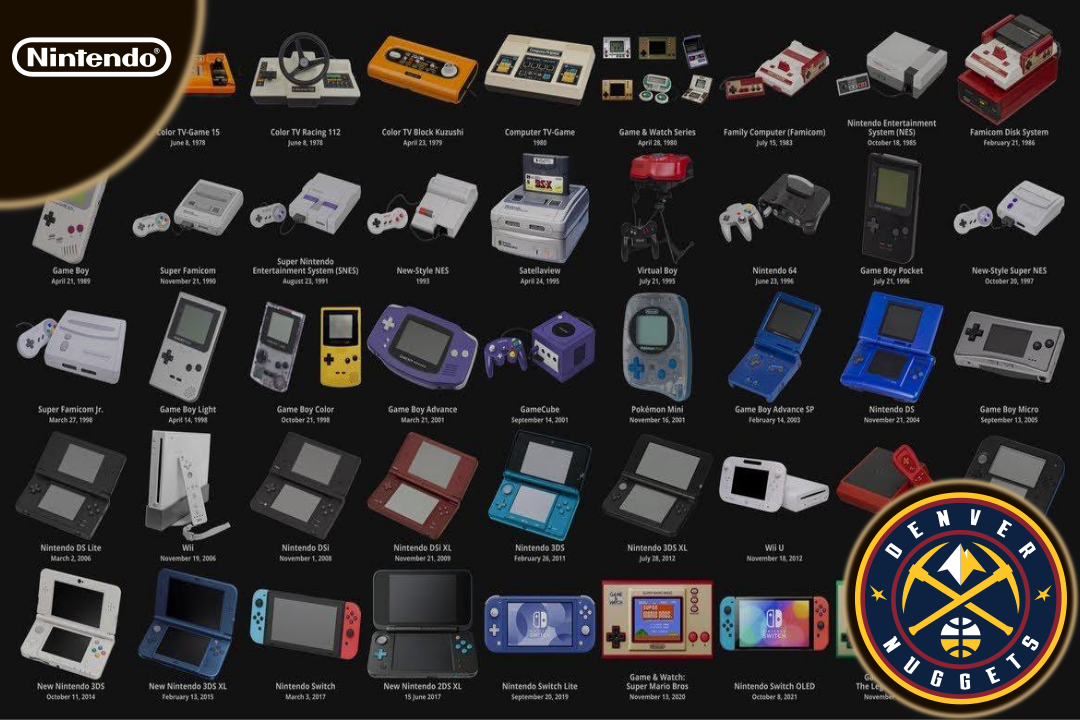

NINTENDO → Doug Moe’s Denver Nuggets (1980’s)

Nintendo didn’t begin as a tech giant. They began as a playing-card company in Kyoto — about as far from the console wars as you could get. But they catapulted themselves into a global entertainment powerhouse by building a culture around play. Where Microsoft and Sony lost money on every console chasing raw performance, Nintendo sold novelty at a profit in every console generation.

That’s Doug Moe’s Nuggets to the bone. Denver couldn’t outspend coastal markets or outmuscle the giants of the era, so they doubled down on entertainment as identity. Moe took the “Passing Game” offense he inherited from Dean Smith and updated it for altitude, speed, and audacity. He pushed pace before “pace and space” had a name — sprinting the ball up the floor so quickly the defense never had time to fossilize. His players operated under a simple two-second rule: move, pass, or shoot, but don’t let the ball stick. The result was constant motion, instinctive reads, and raw entertainment value.

He empowered shooters like Michael Adams decades before the league embraced the 3-point revolution. He embraced offense over orthodoxy, leading the NBA in scoring six times and producing the highest-scoring game in league history in 1983. And while defense remained negotiable, joy never was. Moe built a system where fans didn’t show up for the standings — they showed up for the show.

And in true Nintendo fashion, Denver did more with less. A small-market franchise became a national curiosity thanks to scoreboard explosions. Coaches from Mike D’Antoni to Steve Kerr would later refine concepts Moe sketched first, proof that Denver’s innovations weren’t just fun — they were foundational.

PAYPAL → Oklahoma City Thunder (2020s)

PayPal didn’t just build a product — they built a network. A constellation of experimenters who treated the entire market like a probability engine. Their advantage wasn’t the tool itself, but the volume of trials running through the system and the compounding network effects that followed. Every new user made the network more valuable. Every new experiment made the strategy smarter. PayPal wasn’t engineered for certainty — it was engineered for optionality.

Just as theOklahoma City Thunder under Sam Presti. His approach was disruptive because it rejected the idea of linear planning. He collected draft picks the way PayPal collected nodes — absorb bad contracts, facilitate three-team deals, take the calls no one else wanted, and use the excess to buy low on undervalued players from stressed markets. The roster became a laboratory. Roles shifted, lineups churned, and the organization accumulated years of data on value, development, and fit. Structured iteration crossed with game theory and discipline.

And just as PayPal’s network effects accelerated success, OKC’s hoard of picks created a talent-dense ecosystem that allowed them to run a style no shallow roster could sustain. The Thunder play a hybrid identity: fast enough to bend the floor, long enough to choke off passing lanes, versatile enough to switch and swarm without losing pace. You can only run that system if you have a deep pool of near-perfect pieces.

The Thunder didn’t stumble into Shai Gilgeous-Alexander. They iterated their way to inevitability. The best version of their roster wasn’t discovered — it was converged on through thousands of decisions, each one nudging the network toward its optimal shape. It’s PayPal in basketball form: optionality as architecture, experimentation as competitive edge, and the belief that with enough at-bats, the outlier outcome stops being luck and starts becoming design.

Most Innovators Fail

There are two kinds of failure in innovation. The first belongs to the companies and teams who chased the wrong idea entirely — the ones who built something the world didn’t want or didn’t need. Moviepass.com and Virgin Galactic didn’t fail because they had unlucky timing, their idea simply never penciled out.

The second kind is more informative but harder to swallow. These are the innovators who had the right idea but ran out of time — too early, too small, too fragile, or simply too unlucky. Their failures aren’t indictments of their vision. They remind us that the only thing separating visionaries from crackpots is a finish line of proof.

When Jobs sold fifty Apple I computers he didn’t yet know how to build, he was committing the same category of sin Elizabeth Holmes would commit decades later at Theranos: promising a future that wasn’t real. The difference wasn’t the ethics, it was the outcome. Jobs beat the buzzer and became a visionary. Holmes missed it and became a villain. Silicon Valley was built on lies, but you can’t show up late.

BlackBerry lived on the same edge. For a decade they were untouchable: the most secure, most indispensable mobile device on the planet, built for speed, certainty, and communication. They had already solved the problem the world cared about. Then the iPhone arrived and reframed the entire category overnight. BlackBerry didn’t fail because their idea was wrong — they failed because the future changed faster than they could. Sometimes you crash into a better innovator.

The innovators in this series lived with those same stakes, each undone by a different kind of mismatch. The early-2000s Kings weren’t wrong — they were early. Their offense needed modern spacing and modern rules to breathe, but without bigs that could truly stretch the floor (they didn’t exist yet.) The Seven Seconds or Less Suns went a step further. They created the space Sacramento never had, but still had to run tomorrow’s game under yesterday’s officiating, a league that still punished speed and rewarded physicality in the playoffs. And the Harden-era Rockets? They didn’t fail because the math was flawed. They failed because they ran into the greatest shooting dynasty ever assembled — Blackberry, meet Apple.

Most startups fail. Most revolutions do too. That doesn’t make them wrong. History rarely rewards the first mover — it rewards the one who finishes. Apple didn’t invent the smartphone any more than Steve Kerr invented pace; they simply proved it worked before anyone else could.

Here’s the thing: this is the story we’re here to tell.

Those Who Would Run the World

This opens a nine-part trek through the visionaries, the madmen, and the believers who dared to push basketball past the redline. We’ll follow the lineage of every team that dared to think different about pacing and spacing.

We begin with Phoenix — the team that tried to turn joy into a system. Then Doug Moe’s Nuggets — the proto-rebels who treated thin air as an accelerant. Sacramento’s Adelman years will teach us the early gospel, beauty before its time. From there: Golden State in revolt, Golden State in enlightenment, Houston chasing certainty through math, and finally the modern Thunder — the heirs to the entire acceleration lineage. These aren’t chapters in a timeline. They’re branches in a family tree.

For each chapter, we’ll drop you straight into the moment when the idea first revealed itself, experiencing the plays as they happened. We’ll let the the architects — coaches, visionaries — explain their system in their own words and through their actions. You’ll meet the players who made the idea physical.

Then we’ll drop you into the action for the team’s most dramatic moments: the stretch when the world had no choice but to acknowledge the brilliance, the moment the idea burned at full brightness, and finally: the game that put the finish line in sight -- did they break through… or break apart?

We’ll close with an autopsy of the wisdom that can be gleaned from failure. Their best ideas prove worth as they live on in modern teams. Their tragic flaws are even more instructional.

What We Might Learn

If you stand behind this bar long enough, you’ll see it sooner or later — the patron’s wistful look as they order another, eyes fixed somewhere a decade behind them. They talk about the business deal they almost landed, the romance that burned hot but flamed out too soon, the chance that almost became a life. You learn to recognize the same ache in every story — the way people lean into the hunt, how their voice brightens when they reach the part where their quarry was in sight. And that’s when it hits you: all of the excitement was in the chase.

Chasing speed often isn’t rational or calculated. Sometimes we run because it feels like freedom. We run because it reveals who we are, and who else can keep up. We run to burn off fear, to be completely in the moment. We run because our dreams burn too bright to walk toward.

Whether it’s Steve Jobs in a garage or Mike D’Antoni letting the game play itself, the lesson is the same: every so often, the universe rewards madmen who have the conviction to race a clock that is against them.

This is a series about basketball. It’s also a series about the mad scientists of the game, about leaders who foster flow through trust, about the players who rose to meet the moment.

This is a series about greatness.

Welcome to Those Who Would Run the World.

Let’s begin.

NO TIME OUT, JUST FLOW

Todd / 120 Proof Ball

If you liked this piece, you’re part of the problem.